[ad_1]

As gold prices have skyrocketed, criminal groups once solely dedicated to the trafficking of drugs and arms have moved into illegal mining.

The activity has become one of the most lucrative criminal economies in Colombia. While just under 30 grams of gold raked in over $2,000 in August 2020, the same amount of cocaine fetched less than $1,250 in Miami. Gold is not only more valuable than cocaine but easier to launder, with a fraction of the risk involved in trafficking drugs.

Illegal gold mining has been a major source of income for NSAGs in Colombia since the late 1990s, when the Central Bolivar Bloc (Bloque Central Bolívar – BCB) of the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC), a right-wing paramilitary force, started to profit from extracting the mineral in the departments of Bolívar and Antioquia.

This was replicated by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC) and the guerrilla National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN), which have also got involved in illegal mining across Colombia.

In the early 2000s, under the first administration of President Alvaro Uribe (2002-2006), the government pushed for mining titles to be granted nationwide in what was known as “the mining locomotive.” This was aimed at large, multinational mining conglomerates, who were granted concessions in areas dominated by Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs). This meant they were unable to operate freely. Simultaneously, illegal mining overseen by these very NSAGs enjoyed explosive growth, often accompanied by violence and environmental destruction.

*InSight Crime has joined forces with the Igarapé Institute – an independent think tank headquartered in Brazil, that focuses on emerging development, security and climate issues – to map out environmental crime in the Amazon Basin. Further instalments of the investigation will be published throughout September. Read all chapters here.

Since then, illegal gold mining has only become more important nationwide. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), illicit mining operations now cover more than 64,000 hectares of land across Colombia. From these, 37,138 hectares exist without permits. The remaining 27,589 are located in indigenous community territories; in areas where a mining contract has been requested; and in zones that are still in the process of becoming special reserve areas for mining. Given that these zones are still in the process of being approved to be used for mining, any type of exploitation there is illicit.

Today, illegal mining in the Amazon region is dominated by NSAGs, largely made up of ex-FARC dissidents. The FARC’s Amazon Front, officially demobilized in 2016, in alliance with the 1st Front, continue to oversee illegal mining along the Caquetá and Vaupés rivers.

Military officials based in the Amazonian city of Leticia revealed that in these areas, the ex-FARC Amazonas Front exerts a great deal of control over local communities. According to the officials, dissidents give local people two stark options: be recruited as fighters or become illegal miners.

In 2019, Colombia’s department of Amazonas did not report any gold had been mined, while Putumayo saw 2,652 grams of the precious metal extracted. The same year, some 135,319 grams of gold were sourced from Guainía.

In 2020, close to 100 illegal gold mining sites were found along the Caquetá, Putumayo and Cotuhé rivers, according to the Amazon Geo-Referenced Socio-Environmental Information Network (RAISG), a consortium of civil society organizations that seek to promote sustainability across the Amazon.

Along these waterways, toxic mercury used to separate gold from sediment contaminates water sources and poisons wildlife. Meanwhile, dredges degrade soils once rich in minerals and stoke river sedimentation across the region. Despite the damage caused, mining in Colombia’s Amazon is little studied, with most published investigations focusing on how this activity takes shape across other parts of the country, including the departments of Antioquia, Chocó, Cauca, Santander, and Bolívar.

Colombia’s Treasure Trove: How Illegal Mining Works in Colombia’s Amazon

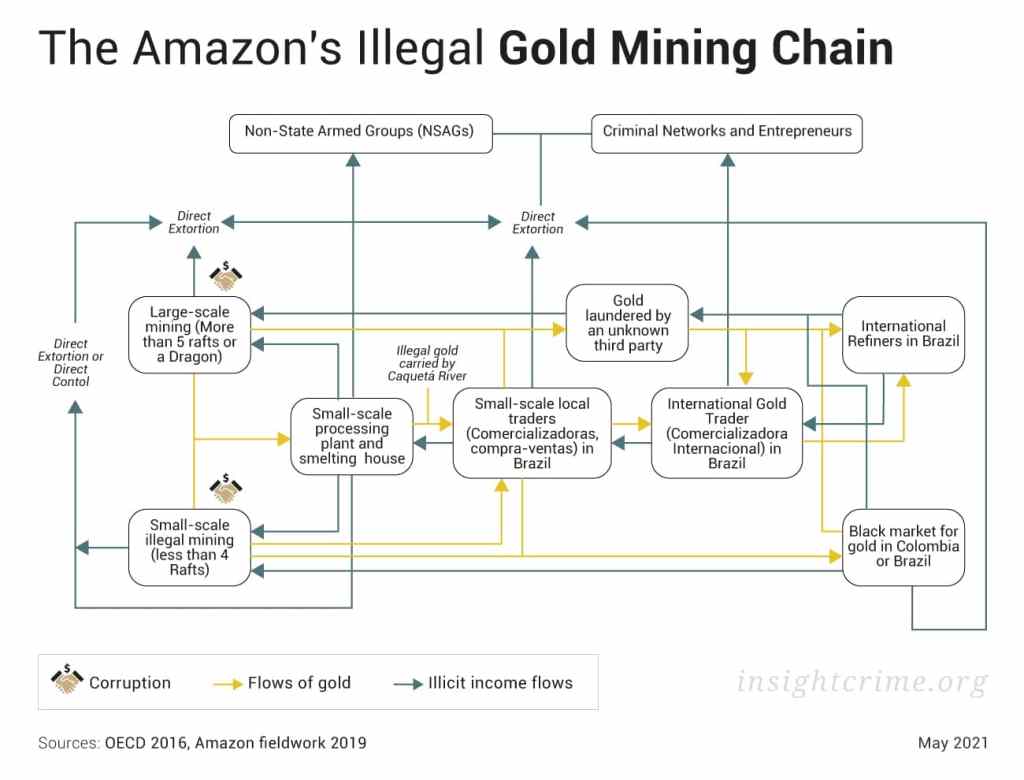

Illegal mining operations devastating Colombia’s Amazon unfold in three principal stages: extraction, transportation and transformation/commercialization.

Mineral extraction across Colombia’s Amazon is not homogenous and varies from department to department, and even from site to site. In 2019, World Wildlife Fund (WWF) revealed that “the majority of mining activities in the Colombian Amazon have focused on removing alluvial sediments with dredges and mini-dredges, with the exception of informal vein mining in low altitude elevations in the Guyana Shield in southern Guainía and Vaupés.”

SEE ALSO: Dirty Business – The Smuggling Pipeline Carrying Mercury Across the Amazon

Equally, more than just gold is mined in the region. Coltan – which is typically used in manufacturing electronic devices such as phones and batteries – is also extracted from Colombia’s Amazonian departments. However, in most departments, gold receives the most attention given its high value.

Primarily, gold is extracted from riverbeds. Unlike in the departments of Antioquia and Chocó, illegal mining in Colombia’s Amazon does not usually take place on land but almost exclusively targets rivers. As a result, mining operations in the region are not limited by departmental borders, as miners move along rivers to search for gold.

Gold mining in Colombia’s Amazon region is not usually carried out using heavy machinery like backhoe diggers in other parts of the country, as these require solid ground on which to operate. Instead, handmade mining rafts are used. Miners sit on floating wooden bases, using motorized hoses to extract up to 40 grams of gold from Amazonian riverbeds per day.

Meanwhile, dredges (or mini dredges) remove silt and other materials from riverbeds and riverbanks, as fragments of the metal are sought out. These machines are more likely to attract the attention of the authorities than rafts but have greater yields of the precious metal.

And “dragons” are perhaps the most important machines used to extract gold. These are devices built on wooden planks with multi-story platforms, on top of which dredges can be found. Dragons increase the overall amount of gold that can be extracted, causing greater degradation than that wreaked by using a dredge alone. Such equipment has been detected across Colombia’s department of Amazonas, having been used to dig into several rivers, including the Caquetá, Puré, Cahuinarí, Querarí, Putumayo and Cotuhé.

Having collated data on incidences of illegal mining along each of these rivers, RAISG detected most sites along the Caquetá River in 2020. According to the organization, there are at least 67 illegal mining sites along the Caquetá River, stretching from the cusp of Colombia’s border with Brazil in Amazonas to the departments of Putumayo and Caquetá.

Each extraction point typically has between one and eight machines. One raft sucking up 40 grams of gold per day can accumulate over 14 kilograms a year, which can make between $150,000 and $200,000 when sold on locally. Army officials claim that dragons used in these rivers are principally brought in from Brazil.

They can reportedly have “up to three floors.” “They are rafts six times the size of a room [of approximately four meters by three meters squared] with several floors and dozens of miners aboard,” the officials confirmed. From these machines, mercury is used to separate gold from river sediment, yielding an amalgam that, after use, is dumped back into the river.

Once the gold is extracted, it then needs to be moved onward. Illicit gold is often smuggled via the Caquetá River to Tefé in Brazil, a route also used to traffic marijuana and cocaine. Military officials based in Colombia’s Amazon said that the Caquetá River is used to move marihuana from the southwestern department of Cauca. They added that cocaine leaving Putumayo is trafficked along the Putumayo River. The officials also explained that the distance between the Caquetá River and the city of Leticia, coupled with a lack of established land routes, means illegal gold is transported out of the Amazon region by air, making it difficult for authorities to catch it in transit.

This gold often finds its way to the hands of “legal” export companies. In 2015, the “Goldex S.A scandal” saw one of Colombia’s largest exporters of the metal accused of laundering both illegally sourced gold and over $1 billion of what was likely drug trafficking proceeds. Goldex reported gold purchases from supposedly legitimate suppliers, who were actually artisanal miners registered under false names, as well as the names of homeless individuals or the deceased. Goldex used shell companies to buy the illegal gold and pass it off as being legally sourced. Goldex exported the precious metal to international markets in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East.

From Criminal Networks to Local Communities

A whole host of actors are involved in illegal mining operations relentlessly extracting minerals from Colombia’s Amazon. Those that make the greatest profits usually never set foot on Amazonian soil but rather handle the sales of gold from their luxury houses in the urban centers.

Actors working in the trade can be divided into four principal categories, much like illegal logging and land grabbing. They are criminal networks/entrepreneurs, NSAGs, the labor force, and facilitators/legal actors. The role of facilitators/legal actors in mining will be explored later in the corruption section.

Criminal Networks and Entrepreneurs

The principal actors driving illicit mining in Colombia’s Amazon today are the patrones, the criminal entrepreneurs or leaders of criminal networks. They have the financial capacity to buy high-cost machinery and often have contact with NSAGs operating in the relevant areas.

Patrones effectively direct and initiate operations, coordinating illicit mining enterprises from start to finish. They hire local miners and operatives; oversee the establishment of new mines; work through subsistence miners to ‘legalize’ illegal gold, and ally with international traders to sell it.

Where illegal mining in Colombia’s Amazon is concerned – especially that taking place along the Caquetá River and in the departments of Amazonas and Caquetá – most patrones appear to be of Brazilian origin. Evidence suggests they principally use Tefé – a Brazilian border town – as their base of operations.

Non-State Armed Groups

Today, illegal mining has become a major source of income for NSAGs in Colombia as the price of gold has skyrocketed. On top of bringing in multi-million-dollar profits, illegal mining has also been used by criminal groups to launder proceeds from other illicit economies, like drug trafficking.

The involvement of such organizations in illegal mining dates back to the 1990s, with paramilitary groups extorting small-scale miners and buying mines. As WWF noted in 2019, “the infiltration of criminal influences in gold production chains in the Amazon is undeniable, yet this is a relatively recent development (approximately since 2000), and its real scope is still unknown.”

SEE ALSO: The Scale of Illegal Coltan Trafficking in Colombia and Venezuela

NSAGs are predominantly involved in the extraction phase, at which point which they collect extortion fees from small-scale miners. Such groups allow miners to extract gold from Amazonian rivers so long as they pay “taxes.”

NSAGs charge extortion fees for machinery, mercury, and gasoline to enter illegal mining sites, according to an army official in the city of Leticia, Amazonas. In some cases, flat taxes are paid by miners simply to be able to operate in a territory controlled by an NSAG. In other cases, a percentage is added on to the standard fee per each piece of machinery brought into the territory. These taxes may be paid in gold itself rather than cash.

Some NSAGs have taken a more direct interest in the gold buried in the region’s rivers, overseeing mining operations themselves. As WWF reported in 2019, “since the 2000s, illegal armed groups like the FARC, the ELN, and paramilitary groups have adopted gold mining as a source for income, complementing other illegal activities like extortion and coca trafficking.” Such groups include the ex-FARC 1st Front and the Amazonas Front.

Labor Force

Local miners or Indigenous people based close to mining sites are usually hired to extract gold from the riverbed, often working 12-hour shifts. They sit at the bottom of the chain, receive the lowest financial reward from the activity and often work under the close watch of NSAGs.

In some cases, members of local communities enter into agreements, either voluntary or under threat, with those orchestrating and financing illicit mining in Colombia’s Amazon. As WWF previously noted, “voluntary or coerced agreements between mine owners, normally from other regions, and Indigenous communities in the mid and Lower-Caquetá River have left local communities at an impasse for how to cope with the expansion of mining in their lands.” This often leads to divisions in the communities, a trend echoed in other parts of the Amazon, including along the Putumayo and Cotuhé rivers.

Local miners and Indigenous people involved in the trade are no match for the military capacity and power of the NSAGs operating in the region. Brazilian miners pay bribes to ex-FARC dissidents in Colombia’s Amazon in exchange for being left to operate in peace.

*InSight Crime has joined forces with the Igarapé Institute – an independent think tank headquartered in Brazil, that focuses on emerging development, security and climate issues – to map out environmental crime in the Amazon Basin. Further instalments of the investigation will be published throughout September. Read all chapters here.

[ad_2]

Source link